He is like a shadow; like a phantom. Obscured by the mists of time and legend. Death has removed from us all means of finding someone today who could contribute some colour to our drab and faded depictions.

The itinerant musician. The walking bluesman. Travelling along the Delta trails, jumping freight trains, instrument of choice strapped to his back. Playing his music then moving on. For so long, we saw not his face, apart from the features of imagination. We glimpsed only his outline. His silhouette.

An unsubstantial suggestion of the man.

There are moments when desperate afficianados would get witnesses, while they still breathed, to give ageing descriptions to composite artists to try and bring him back into the light. To give him an identity and a face beyond the anonymity of the voice alone.

Is the voice not enough? The music? To convince us of one who once was?

Can we not envisage that he was a man like us, who lived in context and not a vacuum?

All bones and little meat. We try to reanimate him with stories, both credible and fantastical.

The musicians in the crowded juke joint, taking a rest from the sweat-filled hovel. Outside, having a smoke in the balmy, southern air. Somebody comes out, interrupting their brief respite, imploring them to come back in to take the guitar off the young guy whose incompetence is driving everybody mad.

And such a racket you never heard!

It is the same youth who habitually turns up to listen to them play, to watch them play. Just sits there observing their hands.

Months go by. Another night. Once again laying down the music, the men drinking, the women gyrating, and in comes the lad. Young Robert Johnson. Only this time he is armed with his own guitar, much to the merriment and mirth of those present. But now he plays. How he plays. His new found ability is greeted with astonishment, and when he sings, Come On In My Kitchen, men and women are moved to tears, and the way is now set for tales to be spun and a legend to run and run until it outstrips fact and the life of its subject.

The Faustian pact; the aspiring musician; the crossroads; midnight.

The man in the dark suit (we all know who he is), takes the guitar, tunes it, plays a few melodies, hands it back with a pleasant damning of the soul.

This must be so. It explains everything.

Long after his death, the stories continue to be told, encouraged by some of Johnson’s cut records: Me And The Devil Blues; Crossroads; Preaching Blues (Up Jumped The Devil), Hellhound On My Trail. His life, his musicianship, all will be forever swept up in a cloud of incredulous tales and romantic mystery.

They dovetail nicely with some of the few anecdotes we have.

The women:many women. They wake in the middle of the night to find their errant lover sitting by the window, soundlessly fingering guitar chords by moonlight. On realising that they are awake he immediately ceases.

When playing in public he shields his hands as he makes the chords, turning his back if he feels a fellow musician’s eyes upon him. There is a secrecy about his craft.

He left us a scant selection of his repertoire-recordings made in ’36 and ’37. Forty two recordings of just twenty nine songs. We still can’t see his hands.

The music is the only thing we can be sure of. His authenticism exists only in that inflected voice, that masterful playing. Even his date of birth is questioned, as we try to fix him rigidly in time and place.

Then comes the moment when surely all will be revealed. An emissary is sent into the deep South to locate him, sent by someone who has listened to those obscure recordings, and wants him to headline a concert at Carnegie Hall, no less.

Robert Johnson-it is time to emerge from the shadows and take your rightful place in front of an appreciative world.

Except, it is too late. All that is located are conflicting tales of the singer’s death shortly before. Instead of being recognised and celebrated, he is memoralised at the concert, two of his recorded songs played to the audience, still blissfully unaware of the enormity of their loss. Unaware of a death that goes by many stories, but falls under one verdict:murder.

We imagine him in another joint, playing for the people, playing to the women. He is handed whisky, laced with poison by a jealous husband, and begins to fall ill. The crowd don’t believe him, and he plays on, as they brush aside his protestations that he is too sick. He plays on, dying. Those secret chords, that haunting voice. One last time. But then he is too ill to continue, and a familiar, dark suited figure is now among the audience.

Johnson takes three days to die. Crawling on his hands and knees and barking like a dog. Even his final moments have an unsubstantiated feel about them. Still shrouded in mystery, there are three graves that lay claim to him.

The guitar has now fallen ever silent, but the stories take up speed.

His stature grows, his reputation grows, the adulation grows. Yet still we know little about him. Just tall stories spun by those thrust into the limelight, clutching at memories now decades old, embellished to please the questioner.

Then, in 1968, for the first time, evidence is found. A birth certificate, the first documentation, makes him real. He is a flesh and blood figure after all. Born of a woman and having walked this earth. He is not a construct of imagination and myth.

Again, in 1973: a death certificate. But, maddeningly, perversely, a cause of death isn’t given.

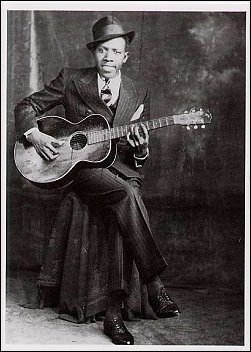

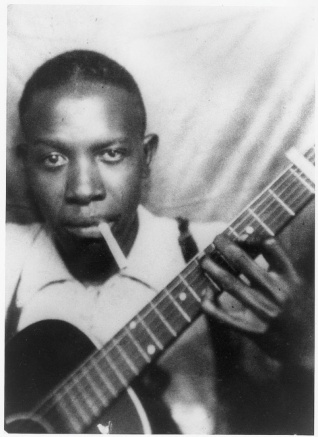

But then, in that same year, the Holy Grail of blues folklore is found. At the end of an arduous quest, two photographs are discovered, thirty five long years after his death. They aren’t widely published until the late 80’s, and when they are, our phantom finally has a face. He emerges from the cloaking veil of superstition and anonymity, bowing shyly before his adoring public.

We stare and stare. Looking for signs. Doubting our eyes. He isn’t a vampire, or a ghost, whose likeness cannot be captured by a lens. He is a man. He is us.

Wearing a pin striped suit that belonged to a nephew who had joined the military. Nothing sinister or devilish here.

There is a later find, only authenticated in 2011, of Johnson with fellow bluesman Johnny Shines. In the way of all things connected to him, some question the identification while others seize it possessively.

Though now our hero has a face, much remains elusive, and will always do so. When we look back over the many years, and try to make sense of his story, ordering it in a way that satisfies, it is like trying to lay a glove on a phantom.

History only gives up so much.

For those of you who appreciate irony, consider this: the most famous of all the bluesmen is the one that we know the least about. What is the cause, and what the effect?

You may bury my body down by the highway side

So my old evil spirit, can catch a Greyhound bus and ride.

Reblogged this on rennydioknodotcom.

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow. What a story! Thanks for this great post on Robert Johnson. His life would make an interesting movie (what little we actually know of him).

LikeLike

I remember a film in the 80’s called Crossroads, which I think (my memory of it is a bit sketchy) was inspired by the Johnson story, but not about Johnson. More a modern (then ) teenage kid. I would like to rewatch it now with a greater perspective.

LikeLike

Perfect!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reading Michael.

LikeLike